Non-violence as an ideology adopted by social movements is a relatively new phenomenon. While people have used both violent and non-violent methods throughout history in struggles against oppression, depending on circumstances, it was not until the late 19th century that non-violence came to be promoted as a philosophy applicable to political action. By the early 20th century, groups began to emerge claiming nonviolence was the only way to establish a utopian society. Most of these groups and their intellectuals derived their philosophies from organized religions such as Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Within these religions were sects that advocated pacifism as a way of life. Often overlooked in critiques of pacifism, this religious origin is an important factor in understanding pacifism and its methods (i.e., missionary-style organizing, claims of moral superiority, appeals to faith and not reason, etc.).

Ironically, considering that the most demonized group by pacifists today are militant anarchists, the leading proponents of pacifism in the 19th century also proclaimed themselves as anarchists: Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy (as would Gandhi). In 1849, Thoreau published his book Civil Disobedience, which outlined his anti-government beliefs and non-violent philosophy. This, in turn, influenced Tolstoy, who in 1894 published The Kingdom of God is Within You, a primer on his own Christian pacifist beliefs.

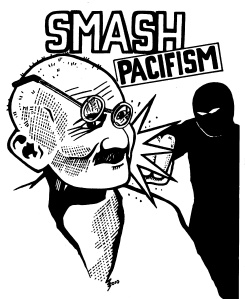

The idea of non-violence did not gain a large following, however, and indeed the 19th and early 20th centuries were ones of widespread violence and social conflict throughout Europe and N. America, as well as in Asia, Africa, and South America. The first significant movement to emerge proclaiming pacifism as the only way was led by Mahatma Gandhi. It is based on this that the entire pacifist mythology of nonviolent struggle is formed, with Gandhi as its figurehead. Yet, Gandhian pacifism would still be seen as a strictly ‘Third World’ peasant phenomenon if it were not for Martin Luther King’s promotion of it during the Black civil rights struggle in the US during the 1950s and ’60s. Today, there are many well intentioned people who think they know the history of Gandhi and King. They assume that nonviolence won the struggle for Indian independence, and that Blacks in the US are equal citizens because of the nonviolent protests of the 1950s.

Pacifist ideologues promote this version of history because it reinforces their ideology of nonviolence, and therefore their control over social movements, based on the alleged moral, political, and tactical superiority of nonviolence as a form of struggle. The state and ruling class promote this version of history because they prefer to see pacifist movements, which can be seen in the official celebrations of Gandhi (in India) and King (in the US). They prefer pacifist movements because they are reformist by nature, offer greater opportunities for collaboration and co-optation, and are more easily controlled.

Even recent history is not immune from this official revisionism. The revolts throughout North Africa and the Middle East in early 2011, referred to as the “Arab Spring,” are commonly understood to have been but the most recent examples of nonviolent struggle. While it was not armed, the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere, saw widespread rioting and attacks against police. In Egypt, where several hundred people were killed in clashes, nearly 200 police stations were arsoned and over 160 cops killed, in the first few months of the revolt. Taking their cue from the “Arab Spring,” many Occupy participants also parroted the official narrative of nonviolent protest and imposed pacifism on the Occupy Wall Street movement, which began in the fall of 2011.

But this narrative didn’t start with Egypt, it began with Gandhi and was modernized and popularized by King. Although there now exist a number of excellent critiques of pacifism, including Ward Churchill’s Pacifism as Pathology, and Gelderloos’ How Nonviolence Protects the State, they do not focus directly on the campaigns of Gandhi and King, the foundations and roots of pacifist ideology. In fact, it is their historical practise, and indeed the very actions and words of Gandhi and King themselves, that most discredit pacifism as a viable form of resistance. For this reason they are the focus of this study.

Link to Download

Non-violence as an ideology adopted by social movements is a relatively new phenomenon. While people have used both violent and non-violent methods throughout history in struggles against oppression, depending on circumstances, it was not until the late 19th century that non-violence came to be promoted as a philosophy applicable to political action. By the early 20th century, groups began to emerge claiming nonviolence was the only way to establish a utopian society. Most of these groups and their intellectuals derived their philosophies from organized religions such as Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Within these religions were sects that advocated pacifism as a way of life. Often overlooked in critiques of pacifism, this religious origin is an important factor in understanding pacifism and its methods (i.e., missionary-style organizing, claims of moral superiority, appeals to faith and not reason, etc.).

Ironically, considering that the most demonized group by pacifists today are militant anarchists, the leading proponents of pacifism in the 19th century also proclaimed themselves as anarchists: Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy (as would Gandhi). In 1849, Thoreau published his book Civil Disobedience, which outlined his anti-government beliefs and non-violent philosophy. This, in turn, influenced Tolstoy, who in 1894 published The Kingdom of God is Within You, a primer on his own Christian pacifist beliefs.

The idea of non-violence did not gain a large following, however, and indeed the 19th and early 20th centuries were ones of widespread violence and social conflict throughout Europe and N. America, as well as in Asia, Africa, and South America. The first significant movement to emerge proclaiming pacifism as the only way was led by Mahatma Gandhi. It is based on this that the entire pacifist mythology of nonviolent struggle is formed, with Gandhi as its figurehead. Yet, Gandhian pacifism would still be seen as a strictly ‘Third World’ peasant phenomenon if it were not for Martin Luther King’s promotion of it during the Black civil rights struggle in the US during the 1950s and ’60s. Today, there are many well intentioned people who think they know the history of Gandhi and King. They assume that nonviolence won the struggle for Indian independence, and that Blacks in the US are equal citizens because of the nonviolent protests of the 1950s.

Pacifist ideologues promote this version of history because it reinforces their ideology of nonviolence, and therefore their control over social movements, based on the alleged moral, political, and tactical superiority of nonviolence as a form of struggle. The state and ruling class promote this version of history because they prefer to see pacifist movements, which can be seen in the official celebrations of Gandhi (in India) and King (in the US). They prefer pacifist movements because they are reformist by nature, offer greater opportunities for collaboration and co-optation, and are more easily controlled.

Even recent history is not immune from this official revisionism. The revolts throughout North Africa and the Middle East in early 2011, referred to as the “Arab Spring,” are commonly understood to have been but the most recent examples of nonviolent struggle. While it was not armed, the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere, saw widespread rioting and attacks against police. In Egypt, where several hundred people were killed in clashes, nearly 200 police stations were arsoned and over 160 cops killed, in the first few months of the revolt. Taking their cue from the “Arab Spring,” many Occupy participants also parroted the official narrative of nonviolent protest and imposed pacifism on the Occupy Wall Street movement, which began in the fall of 2011.

But this narrative didn’t start with Egypt, it began with Gandhi and was modernized and popularized by King. Although there now exist a number of excellent critiques of pacifism, including Ward Churchill’s Pacifism as Pathology, and Gelderloos’ How Nonviolence Protects the State, they do not focus directly on the campaigns of Gandhi and King, the foundations and roots of pacifist ideology. In fact, it is their historical practise, and indeed the very actions and words of Gandhi and King themselves, that most discredit pacifism as a viable form of resistance. For this reason they are the focus of this study.

Link to Download